“Donnery hides secret scars in the folds of her maternal forms. Carter leaves a needle threaded as a reminder that we are never finished making and remaking ourselves. Flannery halts us deftly with a reminder that everything we need has always been right there, inside us, and beside us, all along.””

OCTOBER 2024

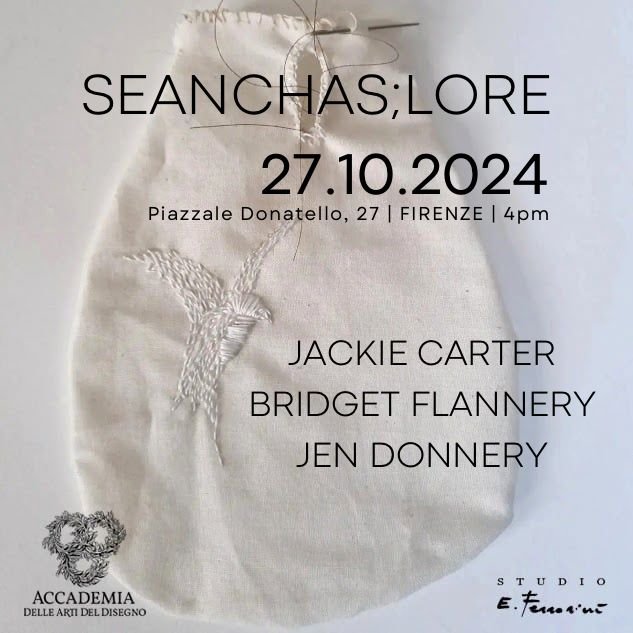

Seanchas; Lore in Florence Atelier Enrico Ferrarini, Piazzale Donatello, 27, Firenze

I have just returned from an incredible few days installing and opening the latest phase of “Seanchas; Lore” in Atelier Enrico Ferrarini , Florence.

It has been a unique opportunity to show my work alongside that of Jackie Carter and Bridget Flannery. Nurturing a relationship between Irish and Italian artists, we enjoyed many lovely conversations with friends old and new who joined us at the reception in such a beautiful and historic setting. Once the studio of painter Tito Conti and now lovingly restored by Enrico Ferrarini, its stunning window provides the perfect backdrop for Bridget’s “Bruscáin agus bigíní/Fragments and rags”.

Publication of the poignant accompanying essay by Cristín Leach is imminent and we are very excited to bring the show back to Ireland after its two week run in Italy.

Huge thanks to the following;

Enrico Ferrarini, The Accademia Della Arti Del Disegno, Jackie Carter, Bridget Flannery RIP, Robert Frazier, Damer House Gallery, Cristín Leach, Laois Arts, Laois County Council Arts Office, The Office for the of State for international Development and Diaspora.

To those who generously allowed me to borrow purchased pieces for the occasion.

And of course to our families and the lovely Cecilia without whose support and hands on help we would be lost!

June 2024

SUMMER EXHIBITION, ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS, BURLINGTON HOUSE, PICCADILLY, LONDON

I’m delighted to have had “Reclaimed” selected for this year’s prestigious Summer Exhibition at the RA. The Lecture Room has been curated by sculptor Veronica Ryan (RA Elect) who has chosen to paint its walls in turmeric yellow and display works on trestle tables and shelves instead of traditional white plinths. Varnishing Day was a special experience I will treasure. The show will run from 18th June until the 18th of August

April 2024

SEANCHAS; LORE, DAMER HOUSE, ROSCREA, TIPPERARY

Sadly, we lost Bridget Flannery days before unveiling her beautiful work in our three woman show, Seanchas; Lore in the stunning Damer House Gallery, Roscrea. I couldn’t feel more privileged to share a space with Bridget and Jackie Carter.

To mark the occasion of Bridget’s swan song, it felt appropriate to approach the talented writer, Cristín Leach to compose an essay in response to Seanchas Lore. Cristín’s sensitive and thought provoking piece can be read here;

On Seanchas; Lore

By Cristín Leach

LET’S begin at the top of the house and with the Irish words painter Bridget Flannery placed above the text she wrote to accompany her work in this three-person show: Bruscáin agus bigíní; Fragments and rags. The Irish comes first and rings somehow messier, more complicated, and more deeply layered with onomatopoeic implications of detritus and small, ephemeral things, than the English phrase does. The artist writes in English, of the ‘textures’ of abandoned ancestral homes, of ‘bowls and curtains to hold and veil’, of the ‘earth pigments of known places’.

In Gallery 3 on the third floor of Damer House in Roscrea, County Tipperary, Flannery’s work dances with the concept of home as made and remade by the women who married into lands not their own (when have they ever been?), and with the legacies of generations of mothers forming new identities of self with which to feed and root the next generation who will call each next, new, old place home; and it will be. Home is where people make place. Outside Gallery 3, on the third floor of this 18th century grand residence turned heritage centre, American visitors tour the historical farm implements and household items on display. Inside Gallery 3, Flannery has placed bowls made like cracked eggshells, drapes painted with bodily fluid tones of dried blood, clear seeping, and the charcoal dust of hearths, and a series of small abstract paintings formed of land hues.

At the black-painted fireplace, missing its surround, Flannery’s bowl-shells spill from the empty grate, piled into each other and tumbling as if descending from the flue; like birds’ nests petrified, like votive cups. The metal vent hinged at the back of the hearth is cracked open, with chimney detritus lodged behind. The artist’s hands have twisted a knotted twig into a loop to hold some muslin, patched and ravelling at its unhemmed edge.

From the ceiling, one soot-black paper bowl dangles from a black thread attached to the picture rail up high. It sways slightly in the breeze caused by a visitor’s presence. Denuded hearth and plaster moulding recall the once intended domestic role of this room, and this building. A three-storey over basement family home built by a wealthy heir in the 1730s, barely lived in, leased then sold as an army barracks (more than once), a school for boys, a TB sanatorium, a library; rescued from demolition, restored and standing still, nine sash windows broad, with a remarkable solid symmetry to its form.

In this bright room with ceilings eleven foot tall, Flannery’s bowls trail from the hearth towards layers of translucent fabrics, hung like laundry by wooden pegs from indoor lines: almost but not quite a dressing for the window, come loose; almost but not quite bedding, undone; almost but not quite abstract canvases, unstretched; and also, all three of these things. Flannery calls them simply, Hanging Textiles. The fabrics are stitched too, the artist’s presence visible in the pigment gestures and in the knotted and trailing, puckered stitches, sutures like dotted lines on a larger map looking to articulate a territory, or to record a path forged through a life and its interconnected histories.

Some bowls are of paper, and some are fabric, stiffened but fragile, membrane-like still. Called simply, Individual bowls, they include two hybrid branch-stick-bowl-nest-shell works which are held together by wrapped and knotted string, something defiant in their making and their mindfully intentional poise. There is fabric scorched and burnt, evergreen fronds turned brown, moisture wicked out. There is calcification, petrification, preservation.

On the wall, a sequence of Scorched Earth paintings are abstract multimedia works, landscape fragments presented like portholes onto the present from the past, or vice versa. The surfaces are also layered with paper painted, soaked, torn, applied and painted again. There are godbeams and rock strata, tree trunks and mountain edges, densely pressed into intense panels of memory and feeling, snapshots of a bigger place.

This work, which appears first gentle, soft and quietly present, becomes insistent, urgent, vital, the more you look. Flannery’s occupation of this room, even in her physical absence, recalls laundry, flags, menstruation rags, medical gauze, muslin to wrap wounds and bolster resilience and healing. Her bruscáin and bigíní point to scars of the past, gathered as humans progress from homestead and birth bed to breathing our last.

That Flannery was working in a new, expanded way as she prepared for this show says something about wisdom and change. That she passed away six days before the exhibition’s planned opening, aged just 65, says something about human mortality. That the work is among the most evocative and inspiring of her four decade career is moving and sobering. The artist was still painting in her hospital bed. There will be no more new work, which is unbelievable; dochredite. And yet, here is this show, which will travel to Italy and there are more exhibitions including Flannery’s work planned and still to come. Art endures and so, in ways, do we. Bás agus fás; death and growth. Breith agus athbhreith; birth and rebirth. Flannery’s work is not yet done.

In Gallery 2, Jen Donnery’s charcoal drawings stretch ceiling to floor, and speak of matrescence, the birth of the mother. Three full-body nude portraits of a woman who holds herself in a shoulder embrace, legs crossed; a woman who reaches up to tie her long hair; a woman who leans against the wall, her back to us, spine curved to the shape of her contrapposto stance. Here, in this room, the female body is muscular, agile, fulsome, present. Donnery’s eight-foot charcoal and pastel drawings make the post-birth mother monumental, awesome, alive. One drawing hangs over the closed-up fireplace in this domestic room turned gallery: woman as a furnace of fecundity, woman at the hearth of the home.

Matrescence is the process of becoming a mother, a word coined by anthropologist Dana Raphael in 1973, not added to the Cambridge English dictionary until 2022. How many centuries English language speakers have lived without a word to describe this fundamental human occurrence. The closest Irish word for matrescence is aibíocht, which means 'ripeness, maturity', but also 'quickness, cleverness, liveliness'. It feels right that it can also translate as ‘mellowness’ or ‘sharpness’, two ends of the emotional spectrum of motherhood; máithreachas. Matrescence is a re-birth but also a double birth, because the post-birth woman cannot go back and be undone as a mother now, no matter what.

Donnery does not separate her identities as mother and as artist from each other. She is mother-artist, artist-mother. The women in her art are more than one woman, a body drawn and sculpted from images of more than one model, including live sketched nudes, merged with feelings about her own mother-body and experience as a mother of six. The gestures captured on paper and in clay are merged with instinct, memory and emotion until each body depicted tells a story that is personal and shared.

Her ceramic figures are hand-sculpted in course clay, their surfaces fire-glazed in multiple washes of copper oxide, worked at, scratched, fingerprinted, and worn. On a plinth, the ceramic sculpture Soothe makes the mother foetal again, her head wrapped in a fabric headdress or bandage perhaps, her hands curled in close to her neck and chest, wrists bent inwards, spine long, body rounded, her feet as bare as those of her tall drawn companions. There is a question here: how to nurture self, how to mind self, how to protect self, when the job now of the newborn mother is to do all of that for someone else? There are two ceramic pieces in this show. Matrescence II shows the woman seated, head bowed as if in sorrow. Is she low at the loss of self that comes with birth, or in response to the weight of this new burden, a baby or the babies, who remain unseen throughout the show. Motherhood can be a kind of grief, as much as it is a celebration of new life, of a new life for more than one.

Donnery lures us in with familiar feeling references to the classic proportions, poses, and traditions of the female nude in art, updating the tradition from the inside, from a post-birth-body point of view. The maternal forms she places in Gallery 2 and in the atrium just outside are beautiful, stretch-marked, weathered and strong. Standing taller than any woman in the world, rendered solid as a precious effigy on a plinth, the female body becomes an amulet in charcoal and clay. The stony texture of the surfaces of her sculptures, seemingly buffeted by time, make the women who are her subject appear as though part of an ancient line and at once brand new each time, like the process of matrescence itself, when you stop and take a closer look at the very flesh and bones of it.

Jackie Carter’s grandmother was a well-worn, new mother when she died aged 45, leaving seven children behind. Her oldest was 25, her youngest child three. Her headstone read, ‘A Devoted Wife and Mother’. It was 1935. There is only one item in Carter’s show that ever really belonged to Agnes. It is a serving plate, a piece of her grandmother’s ‘china’ passed from generation to generation and kept in the good room, now part of a gallery installation that functions seamlessly as an imagined portrait, ‘a critical fabulation’ as the artist puts it. None of this is real, as such, and yet it all feels absolutely true.

Above the fireplace in Gallery 1, a glass fronted display frame with objects inside is titled “Shine through the gloom and point me to the skies”, Abide with Me (Agnes’s Plate). This is a line from Agnes’s favourite hymn, which was sung at her Church of Ireland funeral. Agnes’s plate is decorated with a blue swallow, echoed in an embroidered version of the bird Carter has made to encase alongside it, trapped in the box.

It’s not hard to imagine Agnes loving that plate, with its delicate, floral edge pattern and well-worn gilding. A serving plate. A good plate. The swallow pattern, a reminder of cycles of loss and return, of lull and regeneration, of servitude to a dedicated role and freedom always beckoning. The blue bird on the plate is on the wing. To us now, this plate is also a reminder of the precious paucity of things: a modestly sized, mass-produced, fancy, British transferware platter.

Carter is a textile artist. On the wall she has pinned The Mourning Shawl (Agnes’s Lost Babies), a black tasselled shawl hung and stitched with words in white thread: ‘She was a Beautiful Baby’. Next to the shawl two figures stand, headless dressmakers dummies dressed side-by-side, a small child and a little woman: I was Three years (Jackie), and I was 45 (Agnes). The toddler wears a stained white dress, layered with visible repairs and the rust of horseshoes, a reminder of the equestrian life Agnes loved. The back is stitched with a loop of horsehair and the words ‘I was three years’ on an appliqué patch shaped like a cloud. The end of the older figure’s sleeve, her handless hand, rests on the child’s upper back. Her white apron is stitched with words at the hem, from her own gravestone: A DEVOTED WIFE AND MOTHER.

In two table cabinets, Carter displays four decorative and practical ‘pockets’ ostensibly made by Agnes, in reality posthumous creations, a spiritual collaboration between grandmother and granddaughter across time. The swallow appears again. The pockets are small pouches attached to short ribbons, with a vaginal slit for an opening, blanket-stitched to prevent fraying, the gap small to prevent treasures falling out once they go in.

The objects in these table vitrines are all labelled with old fashioned brown card and string parcel tags, apparently historical documentation vividly conjuring a domestic geography of ‘found in bedside locker’, ‘found in linen press’, ‘found in outhouse’, ‘found by bed’. The pockets are labelled ‘unfinished’, ‘with treasure from the Round field’, ‘on the birth of a son’. With these words, and these objects, one containing the lost first tooth of the artist’s own son, Carter realises an imaginary world for us in which Agnes can be reborn.

She gives her grandmother pockets to carry her treasures. Women in the early 1900s weren’t meant to have possessions with which they could run. A woman with nowhere to keep what precious things she owns on her person, is a woman tied to the cupboards and drawers of home.

The aesthetic of all of this suits the folklore museum feel and part-purpose of Damer House now. Carter’s installation upends some of the assumptions inherent in this kind of public visitor environment, where material culture is presented as communal heritage, although everyone knows objects are as personal as they are societally, culturally, historically representative, and sometimes even more so. When history pushes to tell stories in broad sweeps, art sometimes works to fill the gaps. Carter’s work is a form of resurrection for her grandmother, as much as it is an act of collaborative autofiction. Because real memories and records were scarce, Agnes’s granddaughter had to delve deep into herself to find her.

In a crack where the edge of the eighteen-pane sash window in Gallery 1 closes, in this once domestic, magnificent, abode, a wild climbing violet has snuck through the frame, making an indoor greenhouse for itself behind the pane of glass, inside where the stories in art are told. It’s paler than its siblings on the sill outside, the purple of its petals bleached by the intensity of the glass-parsed sun, a protected, safe but less vibrant version of itself, un-weathered. It is trapped by the path it has taken, limited in potential for growth, but still looking like a flower, and still growing as one.

There are ways in which all three shows in this three woman show are an honouring of the complicated decisions made by women over time in environments where their lives have sprung. Donnery hides secret scars in the folds of her maternal forms. Carter leaves a needle threaded as a reminder that we are never finished making and remaking ourselves. Flannery halts us deftly with a reminder that everything we need has always been right there, inside us, and beside us, all along.

Although the work will travel to another venue and enter other rooms, it feels important to capture Seanchas; Lore in this its first collective home. Here, where it breathes in rhythm with the walls, excavating something of the living, learning, healing and dying that has taken place on a site occupied by problematic humans since at least 1213, its story told mostly through the ownership lines of men. Here, where the art spills from the hearths, and repopulates the rooms, pressing up against every chimney breast, in conversation with every stone.

©Cristín Leach 2024

2022

THE CO-OPERATIVE HANDS OF FRS

It’s been an honour to create this sculpture, commissioned by the board of FRS to mark the achievements of retiring CEO Peter Byrne. In collaboration with Bronze Art Fine Art Foundry.

Bronze on Limestone Plinth from McKeon Stone

Image credit: Saundra Thompson

THE CO - OPERATIVE HANDS OF FRS, APRIL 2022

BRONZE ART FOUNDRY, DUBLIN

©Jen Donnery 2024